You probably think this will be just another boring Home Page...

...with pictures of me, my husband , our cats , hobbies, etc. About as exciting as Spam(tm). Well, you're not

far wrong. I mean, what can a person blather on about that random

net-surfers could care less about? ...with pictures of me, my husband , our cats , hobbies, etc. About as exciting as Spam(tm). Well, you're not

far wrong. I mean, what can a person blather on about that random

net-surfers could care less about?

There's my family, I suppose. None of them have Home Pages yet,

so you'll have to take my word for their existence. My father,

Morris Wolfe , is a teacher and writer. My mother, Carla McKague , is a lawyer and former mathematician. My sister Jen is a musician and mother of two, and my brother Ben does desktop publishing and has three kids. We're all Mac users,

which prevents arguments on the merits of different systems. so you'll have to take my word for their existence. My father,

Morris Wolfe , is a teacher and writer. My mother, Carla McKague , is a lawyer and former mathematician. My sister Jen is a musician and mother of two, and my brother Ben does desktop publishing and has three kids. We're all Mac users,

which prevents arguments on the merits of different systems.

Do you want to know my early history? I was born in Hamilton,

Ontario on September 14, 1964. I was nauseatingly cute as a small

child, and looked like those paintings of children  with enormous eyes. We moved around a lot, and I went to a number

of different schools. We settled in Toronto when I was ten. From

age six to about eighteen, theatre was my main interest. I took

drama classes, got involved in amateur theatre, and worked part

time at Young People's Theatre. Then in high school , my interest shifted to history and re-enactment . with enormous eyes. We moved around a lot, and I went to a number

of different schools. We settled in Toronto when I was ten. From

age six to about eighteen, theatre was my main interest. I took

drama classes, got involved in amateur theatre, and worked part

time at Young People's Theatre. Then in high school , my interest shifted to history and re-enactment .

I could talk about university

(like puberty, thankfully over). I spent almost as much of my life there

(ten years more or less) as I've spent asleep. Come to think of it...

As a student, I wrote countless papers, culminating in a 100-page thesis on experimental archaeology

which no-one, including myself, is ever likely to read again.

countless papers, culminating in a 100-page thesis on experimental archaeology

which no-one, including myself, is ever likely to read again.

I graduated in 1995 with a shiny new master's degree shortly after

relocating to England. Still, England was full of fascinating history, mild weather (compared to Canada ), and Englishmen with sexy accents. I'd had a lot of friends

in the UK for years, partly through archaeological and museum

work in  Canterbury and York , partly through involvement in Viking reenactment , but mainly from the Usenet newsgroup uk.singles , which I discovered by chance while I was a grad student. Meeting

some of these folks face to face has been amusing, educational,

and in at least one case has led to major changes in my life. Canterbury and York , partly through involvement in Viking reenactment , but mainly from the Usenet newsgroup uk.singles , which I discovered by chance while I was a grad student. Meeting

some of these folks face to face has been amusing, educational,

and in at least one case has led to major changes in my life.

I moved to the UK in June of 1995 to finish my thesis and cohabit

with Pete Bevin, aka the Moose. While I was there, I did some

busking with my lap harp and then found a great job in London doing restoration of antiquities.

We worked mainly on archaeological pieces intended for resale

by antiquities dealers, which is a bit of a shady field, but was

really interesting. I worked mainly on a pair of Etruscan sarcophagi

I nicknamed Charles and Di because the sculptural figures looked

like them. Here 's a similar piece from the Louvre with two figures on top, so

you'll know what I'm talking about. found a great job in London doing restoration of antiquities.

We worked mainly on archaeological pieces intended for resale

by antiquities dealers, which is a bit of a shady field, but was

really interesting. I worked mainly on a pair of Etruscan sarcophagi

I nicknamed Charles and Di because the sculptural figures looked

like them. Here 's a similar piece from the Louvre with two figures on top, so

you'll know what I'm talking about.

Life over

there was pretty good, and I had no plans to return to Canada soon.

I'd still be there if I hadn't been diagnosed with inflammatory

breast cancer in April of 1996. My initial treatment, mainly at

the renowned Women's

College Hospital in Toronto, included six months of high dose chemotherapy

(EC with GCSF), a modified radical mastectomy

, five weeks of daily radiation

treatments and ongoing hormonal therapy with tamoxifen

. I lost all my hair (as you can see ), but it came

back in time for my wedding

in October 1997. Life over

there was pretty good, and I had no plans to return to Canada soon.

I'd still be there if I hadn't been diagnosed with inflammatory

breast cancer in April of 1996. My initial treatment, mainly at

the renowned Women's

College Hospital in Toronto, included six months of high dose chemotherapy

(EC with GCSF), a modified radical mastectomy

, five weeks of daily radiation

treatments and ongoing hormonal therapy with tamoxifen

. I lost all my hair (as you can see ), but it came

back in time for my wedding

in October 1997.

The prognosis for IBC isn't usually very good. I had a recurrence

to the brain in September, discovered just 10 days before the

wedding. Most IBC patients eventually have the disease spread,

but usually to the skin, bones, liver or lung. Brain tumours are

difficult to treat (bad), but as the sole site of disease still

allow the possibility of cure (good). Surgery is normally done

only if there are just one or two tumours in safe  locations, there is no other disease, and the patient is healthy.

Without surgery, the odds of making our first anniversary weren't

good, but there were a lot of tests before we'd know if it was

operable.We weren't able to find out until after the honeymoon. locations, there is no other disease, and the patient is healthy.

Without surgery, the odds of making our first anniversary weren't

good, but there were a lot of tests before we'd know if it was

operable.We weren't able to find out until after the honeymoon.

The wedding went ahead at the Elmwood, formerly a private women's

club, which has a wonderful atmosphere and helpful staff. The

bride wore garnet and gold, the fecund matron of honour wore hunter

green, and the menfolk wore double breasted tuxedos with garnet

and hunter waistcoats. The minister who married us is an old friend of mine, a tiny Scotswoman with flaming

tresses. We had 85 guests for a sit-down dinner. The honeymoon

was at Sandals Ocho Rios, in Jamaica. I was on high doses of steroids

and we were under a lot of stress, but we still managed to have

a great time. We went snorkeling, horseback riding in the ocean,

climbed Dunn's River Falls, and spent a lot of time relaxing in

or next to the resort's three pools. married us is an old friend of mine, a tiny Scotswoman with flaming

tresses. We had 85 guests for a sit-down dinner. The honeymoon

was at Sandals Ocho Rios, in Jamaica. I was on high doses of steroids

and we were under a lot of stress, but we still managed to have

a great time. We went snorkeling, horseback riding in the ocean,

climbed Dunn's River Falls, and spent a lot of time relaxing in

or next to the resort's three pools.

I was very lucky and the tumour was solitary and operable. Surgery

(performed while I was awake) was October 27, with radiation about

a month later. It took a few months to regain my energy, more

for my hair to come back a second time, and I was left with some

residual clumsiness of the right hand, but overall I felt well

again six months after rediagnosis. I was able to work part time

doing web graphics, I joined a dragon boat team for breast I was very lucky and the tumour was solitary and operable. Surgery

(performed while I was awake) was October 27, with radiation about

a month later. It took a few months to regain my energy, more

for my hair to come back a second time, and I was left with some

residual clumsiness of the right hand, but overall I felt well

again six months after rediagnosis. I was able to work part time

doing web graphics, I joined a dragon boat team for breast cancer survivors, and by the summer of 1998, I started to dare

to hope and make plans again. After all, I was told that 80% of

operable metastatic brain tumours don't come back. cancer survivors, and by the summer of 1998, I started to dare

to hope and make plans again. After all, I was told that 80% of

operable metastatic brain tumours don't come back.

We were feeling pretty good about things, and came into some unexpected

money, enough for a down payment on a house. We found a place

fairly quickly that was pretty luxurious for two, with an open

concept main floor, a jacuzzi in the bathroom, separate studies

and a cathedral ceiling in the bedroom. It's near downtown in

a really  friendly neighbourhood full of film people and kids. I had high

hopes for the garden despite my total lack of experience, but

so far have only managed to keep it from going completely wild

with the help of friends. Unfortunately my holiday from treatment

ended just days after we moved in. friendly neighbourhood full of film people and kids. I had high

hopes for the garden despite my total lack of experience, but

so far have only managed to keep it from going completely wild

with the help of friends. Unfortunately my holiday from treatment

ended just days after we moved in.

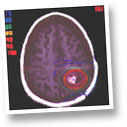

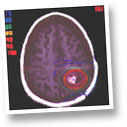

The tumour recurred in exactly the same place in September 1998.

The surgeon wasn't encouraging about more surgery given the risk of disability, so I opted for Stereotactic Radiosurgery, a focused

radiation blast to the tumour. 95% of the time, it controls tumour

growth for at least a year or two, but after just a few months,

the size on the MRI was increasing again. A second awake craniotomy

was done in January 1999, removing all visible tumour and leaving

me with a slight limp. Six weeks later, an MRI showed what appeared

to be regrowth, which was confirmed by increased size on the next

MRI and a sudden worsening of symptoms in late May. of disability, so I opted for Stereotactic Radiosurgery, a focused

radiation blast to the tumour. 95% of the time, it controls tumour

growth for at least a year or two, but after just a few months,

the size on the MRI was increasing again. A second awake craniotomy

was done in January 1999, removing all visible tumour and leaving

me with a slight limp. Six weeks later, an MRI showed what appeared

to be regrowth, which was confirmed by increased size on the next

MRI and a sudden worsening of symptoms in late May.

Two operations had failed, and radiation had failed twice, so

we were left with chemotherapy, often ineffective in the brain.

June and July I took high-dose methotrexate, an intensive in-patient

protocol, but  the tumour doubled in size. August and September I retried the

high-dose EC that had worked in 1996. I knew I'd lose my hair

(the 4th time) on chemo, but this time Pete decided to shave his

head too. We had a party and required that everyone either shave

their head or pay ten dollars, and we donated the money to cancer

research. The tumour didn't respond the tumour doubled in size. August and September I retried the

high-dose EC that had worked in 1996. I knew I'd lose my hair

(the 4th time) on chemo, but this time Pete decided to shave his

head too. We had a party and required that everyone either shave

their head or pay ten dollars, and we donated the money to cancer

research. The tumour didn't respond

October 1999 I started Temodal, an experimental drug that hasn't

been tested yet on breast cancer (even in the brain, it's still

breast cancer). Two months later, another MRI. I was still feeling

reasonably well, although incredibly tired. Comments my surgeon

had made had left me with the idea that some of the mass might

be dead tissue, and I asked for an experimental test that can

distinguish tumour from necrosis, in the hope that things might

not be as bad as they seemed. The day after the tests, I was told

that the mass seemed to be smaller, which was the first good news

in almost a year. Better  news followed a week later, when the other test indicated that

there was no living tumour detectable, that it was all necrosis.

An expert in radiosurgery reviewed all of my 1999 MRIs, and said

it was possibly necrosis all year, a textbook case of post-treatment

damage. news followed a week later, when the other test indicated that

there was no living tumour detectable, that it was all necrosis.

An expert in radiosurgery reviewed all of my 1999 MRIs, and said

it was possibly necrosis all year, a textbook case of post-treatment

damage.

It was days before Christmas and Y2K celebrations, and I had gone

from believing the tumour was resistant to everything and I was going to die, to finding I

was free of disease. Even my normally cautious oncologist was

talking about the possibility of cure. It was a hard shift to

make, even though the news was so good. I had almost lost hope,

and had to relearn to dream. There were a lot of sleepless nights

as my mind made the adjustment. The physical disabilities are

still there. I have limited use of my right hand, a pronounced

limp, and I can only walk a few blocks. I don't know how much

will come back -- I want to play the harp again, to work with

glass and metal, to race in the dragon boat, ride a bike. If I

stay well, I'll resistant to everything and I was going to die, to finding I

was free of disease. Even my normally cautious oncologist was

talking about the possibility of cure. It was a hard shift to

make, even though the news was so good. I had almost lost hope,

and had to relearn to dream. There were a lot of sleepless nights

as my mind made the adjustment. The physical disabilities are

still there. I have limited use of my right hand, a pronounced

limp, and I can only walk a few blocks. I don't know how much

will come back -- I want to play the harp again, to work with

glass and metal, to race in the dragon boat, ride a bike. If I

stay well, I'll  have the time to relearn some of those things. have the time to relearn some of those things.

I'm not able to work right now, and I miss it. I want to feel

productive again. I have a pretty unusual collection of skills

and experience in my CV, but without good dexterity, most of them are impossible. I learned

to read Braille for fun when I was young, I taught myself the

harp in my twenties, picked up some silversmithing, copper enamelling,

calligraphy and art restoration, and while I've been sick I've

developed computer skills, run a mailing list with Pete, and improved

my computer graphics skills.

Menya Wolfe, wolf@bestiary.com , October 27, 1999

|

...with pictures of me, my

...with pictures of me, my  so you'll have to take my word for their existence. My father,

so you'll have to take my word for their existence. My father,

with enormous eyes. We moved around a lot, and I went to a number

of different schools. We settled in Toronto when I was ten. From

age six to about eighteen, theatre was my main interest. I took

drama classes, got involved in amateur theatre, and worked part

time at Young People's Theatre. Then in

with enormous eyes. We moved around a lot, and I went to a number

of different schools. We settled in Toronto when I was ten. From

age six to about eighteen, theatre was my main interest. I took

drama classes, got involved in amateur theatre, and worked part

time at Young People's Theatre. Then in  countless papers, culminating in a 100-page thesis on experimental archaeology

which no-one, including myself, is ever likely to read again.

countless papers, culminating in a 100-page thesis on experimental archaeology

which no-one, including myself, is ever likely to read again.

found a great job in London doing restoration of antiquities.

We worked mainly on archaeological pieces intended for resale

by antiquities dealers, which is a bit of a shady field, but was

really interesting. I worked mainly on a pair of Etruscan sarcophagi

I nicknamed Charles and Di because the sculptural figures looked

like them.

found a great job in London doing restoration of antiquities.

We worked mainly on archaeological pieces intended for resale

by antiquities dealers, which is a bit of a shady field, but was

really interesting. I worked mainly on a pair of Etruscan sarcophagi

I nicknamed Charles and Di because the sculptural figures looked

like them.  Life over

there was pretty good, and I had no plans to return to Canada soon.

I'd still be there if I hadn't been diagnosed with

Life over

there was pretty good, and I had no plans to return to Canada soon.

I'd still be there if I hadn't been diagnosed with

locations, there is no other disease, and the patient is healthy.

Without surgery, the odds of making our first anniversary weren't

good, but there were a lot of tests before we'd know if it was

operable.We weren't able to find out until after the honeymoon.

locations, there is no other disease, and the patient is healthy.

Without surgery, the odds of making our first anniversary weren't

good, but there were a lot of tests before we'd know if it was

operable.We weren't able to find out until after the honeymoon. married us is an old friend of mine, a tiny Scotswoman with flaming

tresses. We had 85 guests for a sit-down dinner. The honeymoon

was at Sandals Ocho Rios, in Jamaica. I was on high doses of steroids

and we were under a lot of stress, but we still managed to have

a great time. We went snorkeling, horseback riding in the ocean,

climbed Dunn's River Falls, and spent a lot of time relaxing in

or next to the resort's three pools.

married us is an old friend of mine, a tiny Scotswoman with flaming

tresses. We had 85 guests for a sit-down dinner. The honeymoon

was at Sandals Ocho Rios, in Jamaica. I was on high doses of steroids

and we were under a lot of stress, but we still managed to have

a great time. We went snorkeling, horseback riding in the ocean,

climbed Dunn's River Falls, and spent a lot of time relaxing in

or next to the resort's three pools. I was very lucky and the tumour was solitary and operable. Surgery

(performed while I was awake) was October 27, with radiation about

a month later. It took a few months to regain my energy, more

for my hair to come back a second time, and I was left with some

residual clumsiness of the right hand, but overall I felt well

again six months after rediagnosis. I was able to work part time

doing web graphics, I joined a dragon boat team for breast

I was very lucky and the tumour was solitary and operable. Surgery

(performed while I was awake) was October 27, with radiation about

a month later. It took a few months to regain my energy, more

for my hair to come back a second time, and I was left with some

residual clumsiness of the right hand, but overall I felt well

again six months after rediagnosis. I was able to work part time

doing web graphics, I joined a dragon boat team for breast cancer survivors, and by the summer of 1998, I started to dare

to hope and make plans again. After all, I was told that 80% of

operable metastatic brain tumours don't come back.

cancer survivors, and by the summer of 1998, I started to dare

to hope and make plans again. After all, I was told that 80% of

operable metastatic brain tumours don't come back. friendly neighbourhood full of film people and kids. I had high

hopes for the garden despite my total lack of experience, but

so far have only managed to keep it from going completely wild

with the help of friends. Unfortunately my holiday from treatment

ended just days after we moved in.

friendly neighbourhood full of film people and kids. I had high

hopes for the garden despite my total lack of experience, but

so far have only managed to keep it from going completely wild

with the help of friends. Unfortunately my holiday from treatment

ended just days after we moved in. of disability, so I opted for Stereotactic Radiosurgery, a focused

radiation blast to the tumour. 95% of the time, it controls tumour

growth for at least a year or two, but after just a few months,

the size on the MRI was increasing again. A second awake craniotomy

was done in January 1999, removing all visible tumour and leaving

me with a slight limp. Six weeks later, an MRI showed what appeared

to be regrowth, which was confirmed by increased size on the next

MRI and a sudden worsening of symptoms in late May.

of disability, so I opted for Stereotactic Radiosurgery, a focused

radiation blast to the tumour. 95% of the time, it controls tumour

growth for at least a year or two, but after just a few months,

the size on the MRI was increasing again. A second awake craniotomy

was done in January 1999, removing all visible tumour and leaving

me with a slight limp. Six weeks later, an MRI showed what appeared

to be regrowth, which was confirmed by increased size on the next

MRI and a sudden worsening of symptoms in late May. the tumour doubled in size. August and September I retried the

high-dose EC that had worked in 1996. I knew I'd lose my hair

(the 4th time) on chemo, but this time Pete decided to shave his

head too. We had a party and required that everyone either shave

their head or pay ten dollars, and we donated the money to cancer

research. The tumour didn't respond

the tumour doubled in size. August and September I retried the

high-dose EC that had worked in 1996. I knew I'd lose my hair

(the 4th time) on chemo, but this time Pete decided to shave his

head too. We had a party and required that everyone either shave

their head or pay ten dollars, and we donated the money to cancer

research. The tumour didn't respond

news followed a week later, when the other test indicated that

there was no living tumour detectable, that it was all necrosis.

An expert in radiosurgery reviewed all of my 1999 MRIs, and said

it was possibly necrosis all year, a textbook case of post-treatment

damage.

news followed a week later, when the other test indicated that

there was no living tumour detectable, that it was all necrosis.

An expert in radiosurgery reviewed all of my 1999 MRIs, and said

it was possibly necrosis all year, a textbook case of post-treatment

damage. resistant to everything and I was going to die, to finding I

was free of disease. Even my normally cautious oncologist was

talking about the possibility of cure. It was a hard shift to

make, even though the news was so good. I had almost lost hope,

and had to relearn to dream. There were a lot of sleepless nights

as my mind made the adjustment. The physical disabilities are

still there. I have limited use of my right hand, a pronounced

limp, and I can only walk a few blocks. I don't know how much

will come back -- I want to play the harp again, to work with

glass and metal, to race in the dragon boat, ride a bike. If I

stay well, I'll

resistant to everything and I was going to die, to finding I

was free of disease. Even my normally cautious oncologist was

talking about the possibility of cure. It was a hard shift to

make, even though the news was so good. I had almost lost hope,

and had to relearn to dream. There were a lot of sleepless nights

as my mind made the adjustment. The physical disabilities are

still there. I have limited use of my right hand, a pronounced

limp, and I can only walk a few blocks. I don't know how much

will come back -- I want to play the harp again, to work with

glass and metal, to race in the dragon boat, ride a bike. If I

stay well, I'll  have the time to relearn some of those things.

have the time to relearn some of those things.